Please wait a few moments while we process your request

Vera Frenkel

Cartographie d'une pratique / Mapping a Practice

Notes from my second Black Book: September to December 1974

Stephen Schofield

October 1, 1974

Imagine Vera Frenkel as a virtual Colossus straddling Montreal and Toronto, one hand in each city, then ask yourself what direction she is facing. The obvious choice would be to have her aligned to the country cartographically, with north at the top. But, as with so many details in the artist's work, she makes the subtle but perversely political choice to eschew the normative viewpoint and holds the map upside down, the Queen City to the right and Montreal à gauche. This early and seminal piece maps out the terrain for the celebrated works to follow. Prepare yourself to read maps upside down, in a mirror and inside out.

September 12, 1974

Vera Frenkel is a storyteller. In her tales of art and life, symmetry exacerbates paradox. Although pioneering technologies provide the frame of her work, the tools she deploys with consummate ease, craft and treachery are her voice and her hands. Her opening lines are always simple and fraught, and she pronounces them in a modulated, clear and frankly sensuous voice. Few of her stories, if analyzed, are to be believed. But that matters little, because we want to believe, we want to both hear her open-throated laugh and see the dart of her tongue punctuate the story as she tells it over again.

Of particular note are Vera's hands; like most people she has two of them. But unlike most people, hers have separate lives. While one moves into the foreground, manicured, languorous and elegant—whether playing the piano, tending a bar, lifting a screen, writing notes or drawing—the muscles of the other are taut, ready to nick, to point, to coax.

October 1, 1974

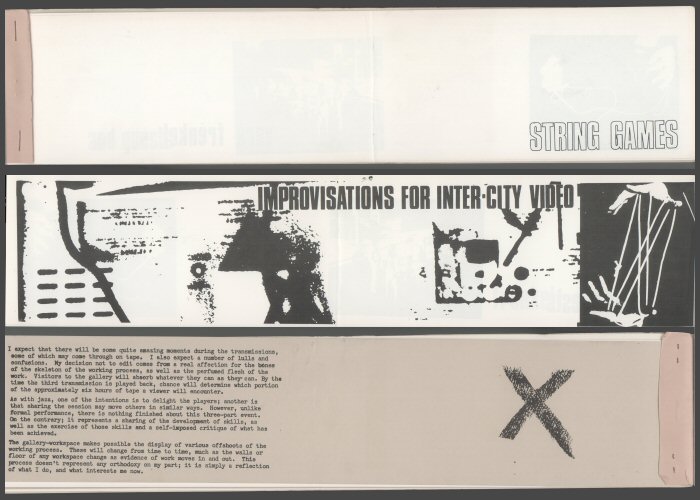

Just as a storyteller's tools must be simple and immediate, a storyteller's methods must be familiar yet fresh. A good story is no place for arch devices. In String Games, Vera Frenkel mapped out three types of simple symmetry she would use time and again to wildly different effects in later works.

September 12, 1974

The easiest to understand is mirror symmetry—at its simplest it's the complementary relationship of the left and right hands. This symmetry defines how Vera's characters interact: Toronto and Montreal, lover and beloved, duellers, victim and executioner, bartender and bar regular. In this reflecting dynamic, each side scrutinizes the other for the detail that makes love flip to repulsion and back. Despite the evident potential of the two city structure of String Games to address the key Canadian love/hate story then and now (4), none of the contributions of the participants recognised either the experience or reality of French Canadian culture. That said, the cat's cradle structure of the String Games can be seen as a metaphor for an interconnected society where all parts are playing together for the game. In this sense it lays the foundation for Vera Frenkel's use of language in the Transit Bar project where the contest of power, identity and empathy is played out by translating, mistranslating or simply not translating the different languages of Mitteleuropa.

October 3 1974

Serial symmetry is a bit different; it is not about complementarity but rather repetition. It is a child laying her left hand over her mother's hand, which lies over the hand of her grandmother. Serial symmetry is about finding the difference in the same. It is also the logic of the cyclical patterns of generations. In later pieces, Vera will develop the same symmetry in the act of translation. In String Games, serial symmetry appears in the set phrases, gestures and sounds we repeat week after week, lending new meaning to the same simple elements by nuanced inflection and timing.

December 10, 1974

The third form of symmetry found in String Games is radial. It is the relationship of a static centre controlling a revolving circle. Think of the right hand pinning down the end of a string while the left takes a pencil at the other end of the string for a walk. We know how to inscribe a circle; however, the key to Vera's work is not the circle but how she teases out the drawing of it; life and art spin around each other like a point and the circle. She knows a few things about the seduction of acceleration and the sweet frustration of slowing down. She also takes the risk of setting off centrifugal or centripetal forces. She tested out centrifugal forces in String Games when she invited us to develop our own games. The same forces govern The Body Missing project, where the strings connecting art to life break and spin off into the madness and disorder of Hitler's art collection. Other times, she lets the centripetal forces compress art and life into a minimal masterpiece of ecstasy. One such moment concludes String Games, as Vera lifts a transparent screen off the television monitor; image and object are concentrated within that thin membrane.

Second half of October 1974

String Games oscillated between extraordinary success and extraordinary failure. It was marked by sequences of remarkable poetry and interminable waits, stunning visuals and technical glitches. Of course, the failures could be attributed to the infantile state of media in the '70s, but that would be missing the point. Whatever the media, Vera Frenkel played dangerously; time and again she set up the rules only to break them herself, generally at the last minute. Certainly we were working intensely on getting the choreography "right," yet when it didn't work, she knew how to draw out laughter, jokes and grimaces and etch them in sharp relief against the mechanics of the piece. The success of this failure lies in the intensity of trying and the sheer moxie of trying to try. Extraordinary success, rare as it is, is easy to imagine, but it takes an exceptional artist to also make an extraordinary failure and Vera Frenkel is such an artist.

Had the choreography run seamlessly and had the Bell Lab cameras documented the entire performance, the piece might never have been such a rich repertory of open business for the artist and for us. Consider Once Near Water: Notes from the Scaffolding Archive. It is not that we believe in the posthumous letter as much as we're touched and drawn, I'd say even seduced, by the artist's need to convince us. The story is too perfect and too well told not to trust her, even when her plea is far from persuasive. Ultimately, believing and playing the game is more empowering than being convinced by it, and this is the strength of Vera Frenkel's practice.

End of October 1974

Stephen Schofield has been showing drawings and sculptures since 1979 notably at the Power Plant, Toronto, the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, the Centre d'art contemporain de Vassivère and the Centre d'art contemporain d'Ivry in France, as well as at the Sculpture Centre, White Columns, in New York. He lives in Montréal where he teaches at the Université du Québec à Montréal. He was awarded the Louis Comtois Prize in 2005 and more recently the Canada Council Studio in New York. He is represented by Galerie Joyce Yahouda in Montréal.

Stephen Schofield

October 1, 1974

Today, October 1, 1974, is my twenty-first birthday. Vera wants to use the movements and patterns of Cat's Cradle for a game on closed circuit TV between Montreal and Toronto. Five people in each city take the positions of the fingers of each hand holding the cradle. So far, we've used numbers, letters, words, names, sentences, gestures, images, sounds and poems.

Imagine Vera Frenkel as a virtual Colossus straddling Montreal and Toronto, one hand in each city, then ask yourself what direction she is facing. The obvious choice would be to have her aligned to the country cartographically, with north at the top. But, as with so many details in the artist's work, she makes the subtle but perversely political choice to eschew the normative viewpoint and holds the map upside down, the Queen City to the right and Montreal à gauche. This early and seminal piece maps out the terrain for the celebrated works to follow. Prepare yourself to read maps upside down, in a mirror and inside out.

September 12, 1974

"My advice is not to let the boys in." (1)

Vera Frenkel is a storyteller. In her tales of art and life, symmetry exacerbates paradox. Although pioneering technologies provide the frame of her work, the tools she deploys with consummate ease, craft and treachery are her voice and her hands. Her opening lines are always simple and fraught, and she pronounces them in a modulated, clear and frankly sensuous voice. Few of her stories, if analyzed, are to be believed. But that matters little, because we want to believe, we want to both hear her open-throated laugh and see the dart of her tongue punctuate the story as she tells it over again.

Of particular note are Vera's hands; like most people she has two of them. But unlike most people, hers have separate lives. While one moves into the foreground, manicured, languorous and elegant—whether playing the piano, tending a bar, lifting a screen, writing notes or drawing—the muscles of the other are taut, ready to nick, to point, to coax.

October 1, 1974

As George M. (2) pointed out, the simpler the rules, the stranger and more varied the possibilities. Hence A Man and a Dog allows for deeper meaning and more leeway than Hamlet...

Just as a storyteller's tools must be simple and immediate, a storyteller's methods must be familiar yet fresh. A good story is no place for arch devices. In String Games, Vera Frenkel mapped out three types of simple symmetry she would use time and again to wildly different effects in later works.

September 12, 1974

"Flounder Murray, flounder" (3)

The easiest to understand is mirror symmetry—at its simplest it's the complementary relationship of the left and right hands. This symmetry defines how Vera's characters interact: Toronto and Montreal, lover and beloved, duellers, victim and executioner, bartender and bar regular. In this reflecting dynamic, each side scrutinizes the other for the detail that makes love flip to repulsion and back. Despite the evident potential of the two city structure of String Games to address the key Canadian love/hate story then and now (4), none of the contributions of the participants recognised either the experience or reality of French Canadian culture. That said, the cat's cradle structure of the String Games can be seen as a metaphor for an interconnected society where all parts are playing together for the game. In this sense it lays the foundation for Vera Frenkel's use of language in the Transit Bar project where the contest of power, identity and empathy is played out by translating, mistranslating or simply not translating the different languages of Mitteleuropa.

October 3 1974

...I think that Vera's Television Things need verbs and conjunctions: "against," "on the other side of," "for his sake," "in spite of," "in" or "at."

Serial symmetry is a bit different; it is not about complementarity but rather repetition. It is a child laying her left hand over her mother's hand, which lies over the hand of her grandmother. Serial symmetry is about finding the difference in the same. It is also the logic of the cyclical patterns of generations. In later pieces, Vera will develop the same symmetry in the act of translation. In String Games, serial symmetry appears in the set phrases, gestures and sounds we repeat week after week, lending new meaning to the same simple elements by nuanced inflection and timing.

December 10, 1974

Second Year: Draw a paper bag- in any state, flat, crumpled, open, whatever.

Third Year: Invent a project using brown paper bags.

Fourth Year: Invent a paper bag. (5)

Third Year: Invent a project using brown paper bags.

Fourth Year: Invent a paper bag. (5)

The third form of symmetry found in String Games is radial. It is the relationship of a static centre controlling a revolving circle. Think of the right hand pinning down the end of a string while the left takes a pencil at the other end of the string for a walk. We know how to inscribe a circle; however, the key to Vera's work is not the circle but how she teases out the drawing of it; life and art spin around each other like a point and the circle. She knows a few things about the seduction of acceleration and the sweet frustration of slowing down. She also takes the risk of setting off centrifugal or centripetal forces. She tested out centrifugal forces in String Games when she invited us to develop our own games. The same forces govern The Body Missing project, where the strings connecting art to life break and spin off into the madness and disorder of Hitler's art collection. Other times, she lets the centripetal forces compress art and life into a minimal masterpiece of ecstasy. One such moment concludes String Games, as Vera lifts a transparent screen off the television monitor; image and object are concentrated within that thin membrane.

Second half of October 1974

My list: Vera's Game

Number: 1st version - To (2) for (4) ate (8), 2nd version 2 (to)

Letter: 1st version - I (eye), c (see) b (be) + p, 2nd version I (eye)

Word: 1st version - Perceiver, does, onomatopoeia, 2nd version picot, 3rd version taciturnity

Name: 1st version - Shah Jahan (6)

Sentence fragment: 1st version - Foundations of Versification, Pyrrhic Victory, 2nd version I think I shall not hang myself today (7)

Poem: 1st version - Rough is the road, your wheel is out of order, (8) 2nd version And murmuring of innumerable bees (9)

Image: Unicorn

Gesture: Turn around

Sound: D sharp

Number: 1st version - To (2) for (4) ate (8), 2nd version 2 (to)

Letter: 1st version - I (eye), c (see) b (be) + p, 2nd version I (eye)

Word: 1st version - Perceiver, does, onomatopoeia, 2nd version picot, 3rd version taciturnity

Name: 1st version - Shah Jahan (6)

Sentence fragment: 1st version - Foundations of Versification, Pyrrhic Victory, 2nd version I think I shall not hang myself today (7)

Poem: 1st version - Rough is the road, your wheel is out of order, (8) 2nd version And murmuring of innumerable bees (9)

Image: Unicorn

Gesture: Turn around

Sound: D sharp

String Games oscillated between extraordinary success and extraordinary failure. It was marked by sequences of remarkable poetry and interminable waits, stunning visuals and technical glitches. Of course, the failures could be attributed to the infantile state of media in the '70s, but that would be missing the point. Whatever the media, Vera Frenkel played dangerously; time and again she set up the rules only to break them herself, generally at the last minute. Certainly we were working intensely on getting the choreography "right," yet when it didn't work, she knew how to draw out laughter, jokes and grimaces and etch them in sharp relief against the mechanics of the piece. The success of this failure lies in the intensity of trying and the sheer moxie of trying to try. Extraordinary success, rare as it is, is easy to imagine, but it takes an exceptional artist to also make an extraordinary failure and Vera Frenkel is such an artist.

Had the choreography run seamlessly and had the Bell Lab cameras documented the entire performance, the piece might never have been such a rich repertory of open business for the artist and for us. Consider Once Near Water: Notes from the Scaffolding Archive. It is not that we believe in the posthumous letter as much as we're touched and drawn, I'd say even seduced, by the artist's need to convince us. The story is too perfect and too well told not to trust her, even when her plea is far from persuasive. Ultimately, believing and playing the game is more empowering than being convinced by it, and this is the strength of Vera Frenkel's practice.

End of October 1974

Tom's Game

Pitch Papers

Pitch Papers

Stephen Schofield has been showing drawings and sculptures since 1979 notably at the Power Plant, Toronto, the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, the Centre d'art contemporain de Vassivère and the Centre d'art contemporain d'Ivry in France, as well as at the Sculpture Centre, White Columns, in New York. He lives in Montréal where he teaches at the Université du Québec à Montréal. He was awarded the Louis Comtois Prize in 2005 and more recently the Canada Council Studio in New York. He is represented by Galerie Joyce Yahouda in Montréal.

© 2010 FDL

(1) Vera Frenkel cajoling a student in our class.

(2) George Manupelli, artist, filmmaker, and professor at York University, Toronto.

(3) Vera Frenkel bantering with Murray Leadbeater.

(4) The performance took place four years after the War Measures Act and five years after bilingualisme came the official policy of the federal government.

(5) My thanks to Julia Grant for sharing Vera Frenkel's mimeographed course notes with me.

(6) Shah Jahan was a great builder of gardens and palaces (Taj Mahal) and collector of Persian miniatures.

(7) A Ballade Of Suicide, G. K. Chesterton.

(8) The Friend of Humanity and the Knife Grinder, George Canning.

(9) Come Down, O Maid, Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Index:

- Presentation

• Introduction, by Sylvie Lacerte

• Foreword, by Katia Meir

• Foreword, by Paul Banfield - Essays

• Sylvie Lacerte

• Heather Home

• Alain Depocas

• Anne Bénichou

• Stephen Schofield

• Vera Frenkel - Resources

• Selected works

• Selected archival documents

• Selected exhibitions

• Selected bibliography

• Online resources

• Acknowledgements

• Credits