Ghana's Highlife Music Collection

A Digital Repertoire of Recordings and Pop Art

One cannot imagine the Ghanaian music world without its highlife music.

Highlife is often described in the African survey as neo-folk or a cross-breed between folk music and imported music. It is indeed the sum total of all that is Ghanaian music seasoned and illuminated by rich endowment from Latino and American music fields, yet the Ghanaian Highlife is unique in itself and successfully interprets the Ghanaian personality.

Why is Ghana highlife so unique and so fascinating? This is simple. Ghana highlife lends itself to easy appreciation. Both the local and the foreigner shake their head or stamp their feet on the floor to rhythm because the highlife rhythm comes directly to them, holding them enthralled and fascinated. The beat becomes familiar to the stranger even if the words are not understood.

The happy atmosphere created by the blending of the various instruments is quite universal. The rhythm is native because it is deeply rooted in the Ghanaian music culture and semblances can be noted in most Ghanaian cultural music lyrics. The Ghanaian highlife music founded on traditional music forms, expresses our traditional feelings and our Ghanaian personality.

One may ask why call it highlife if it is native? To the world, the music is known as highlife and any change will mean something else to the Ghanaian and nothing, perhaps to the outside world. So highlife will ever remain since it does not affect the enchanting and compelling rhythm of the music.

Oscarmore T.A. Ofori, 1971.

1. General introduction by Carmelle Bégin, ethnomusicologist

Highlife music has established itself as one of the most important world music genres of the twentieth century. Born in Western Africa, this dance music develops itself in the colonial time from its African roots (2) and integrates other elements when coming into contact with Western musics. The highlife music evolves principally in an urban environment, where nightclubs, bars and ballrooms attract wealthy customers.

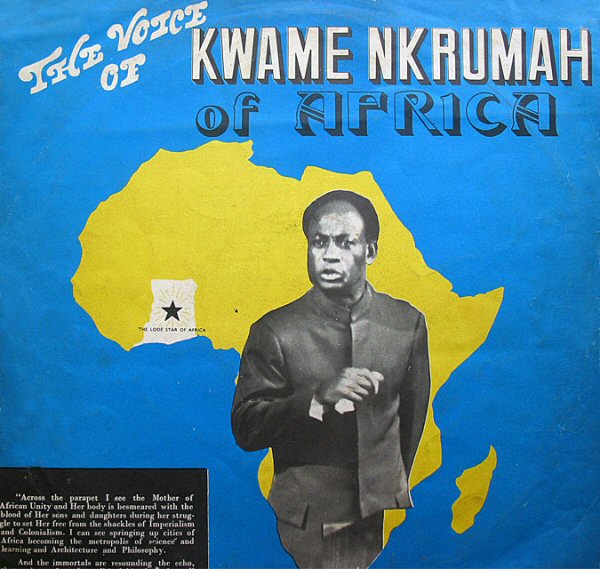

Encouraged and fuelled by all the Senghor, Césaire, Touré and Nkrumah, who advocate their African identity, the highlife music and the concert party – a vaudeville show with which it fuses – adopt vernacular languages to express themselves. During its fight for Ghana’s independence, political leader Kwame Nkrumah proclaims highlife music as Ghana’s national music. Highlife bands accompany him during his tour of African countries to promote his africanization policy: “Africa is for Africans”, he repeats during his famous speech to the freedom fighters.

It is under the reign of Kwame Nkrumah that the Arts Council of Ghana Law was created. Its mission is to protect, stimulate and improve the nation’s cultural expressions and limit foreign influence on music. (3) Thus, new forms of traditional highlife music are born and, paradoxically, the influence of Afro-American music strengthens in West Africa with the return in their country of many expatriate musicians and by the international tours of African-American stars such as Louis Armstrong and James Brown.

In the 1950s, the Ambassador Manufacturing Company (Ghana) Limited of Kumasi, will stand as a local alternative to the disc market which is dominated by foreign companies. Between 1970 and 1990, political instability, the exodus of musicians to Europe and America, the desertion of dance halls, and the introduction of the new digital technologies that provoke the collapse of vinyl, are only but a few of the factors that will contribute to change Ghana’s cultural scene.

2. Places and artists

Following the War of 1896 that subjugates Ghana to the British Empire, regiments station their troops in the coastal cities. There, African troops intersect with Caribbean and British ones who carry along their musical repertoire, which will be adopted by local musicians. In the 1930s, military-inspired orchestras start increasing in large urban centres. (4) Their repertoire offers waltzes, foxtrots and local melodies adapted to the current taste. These bands appear in ballrooms, theatres and cabarets, where members of social clubs ensure these establishments are properly administered.

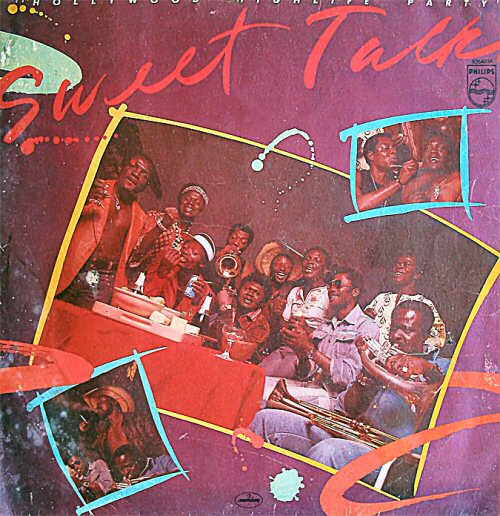

Some of these highlife music and dance halls, which were well-known between the 1920s and 1930s remained in the collective memory. In Accra, people were rushing to the Metropole Hotel, Kit Kat, Tip Toe Gardens, Kalamazoo, and to the Lido Night Club where E.T. Mensah performed among others. In Takoradi, the Zenith Hotel was housing the Broadway Band, and the Princess Night Club invited C.K. Mann to conduct its Carousel Seven. In Kumasi, the Ambassador Garden Hotel sponsored the African Brothers; in Tema, the Talk of the Town welcomed the Sweet Talks. And let's not forget the Napoleon Night Club, which became in 1974 the centre of musical life in Accra. (5)

After the Second World War and the rise of African nationalism, large orchestras, which are deemed too colonial, are left behind for guitar bands and their highlife music. On top of attracting dance-lovers, the tremendous popularity of highlife music can partly be explained by the content of songs that sings praises of political leaders, speaks out against injustices, is inspired by proverbs or religious morality, and ridicules some aspects of society. The vaudeville theatre, also called concert party, which became very popular during the inter-war years, is also an important angle of social criticism. This opéra comique presents a gentleman, a humourous character who is called the joker, and a travestite comedian who embodies a female character. They are usually accompanied by a harmonium and a percussionist.

These instruments are set aside when in 1952 E.K. Nyame merges his vaudeville theatre with his guitar band to create the Akan Trio. This genre will be pursued by a large number of artists, comedians and musicians who will practice their art beyond the 1980s. Influenced by the Africanization movement which comes along with independence, the concert party will abandon its English language roots for local languages, in turn promoting Ghanaian nationalism. (6) Some artists will lend their talent to illustrate in a dramatic and caricatural way the topic of their comedies on billboards or album covers.

4. The independence of Ghana and the golden years of highlife music

E.T. Mensah, the “King of Highlife”, and his Tempos are the post-war years’ big stars. In 1957, the highlife music that was proclaimed Ghana’s national music by Kwame Nkrumah becomes a cultural symbol and a tool of political propaganda. E.K. Nyame – one of Nkrumah favourite performers – E.T. Mensah and his Tempos, Kwaa Mensah and Broadway Band, are only but a few of the artists who will compose songs that praise the country and its leader. (7)

The economic growth that follows independence stimulates social and cultural life and a variety of bands are successful. The Black Beats, the Red Spots, Joe Kelly’s band, the Ramblers, the Stargazers, the Rhythm Aces, and Kwabena Onyina interpret and mix a variety of musical styles: highlife, calypso, jazz as well as ballroom music, and assert themselves on the public scene through tours, 33 rpm records and radio. C.K. Mann will mark the decade of the 1970s by incorporating elements of the music Osode from the coastal region of Cape Coast in the highlife. In the capital region of Accra, the band Wulomei creates a new genre by incorporating for the first time the music from the Ga tradition to the highlife music.

During the 1980s, disco music became very popular, and negatively impacts the night-club orchestras. The emergence of disc jockeys and their mobile discotheques deliver a fatal blow to night-club orchestras. The spectacular popularity of other musical genres, like gospel highlife and hiplife – a fusion of highlife music and hip hop – transforms the cultural scene at the turn of the 21st century. Today, highlife bands are being revived during festivals organized in the major centres, and one still can hear highlife music in some scarce hotels, during weekends or special events.

5. Ghana’s disc industry

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pathé (in France) and Zonophone (in England) studios record the songs of West African artists and distribute their discs in several African countries. In 1928 in London, Zonophone records Kwame Asare (also known as Jacob Sam) and his song “Yaa Amponsah” is the model which establishes a long tradition of highlife songs. (8) During the years that follow, foreign disc production companies, such as Pathé-Marconi, EMI, Gallo-Africa, and many more, establish their headquarters in the large West, East, and South African cities. (9)

We’ll have to wait until the end of the 1950s to see Ghana’s first record production company, Ambassador Records Manufacturing Company (Ghana) Limited. This company and some others will produce 78 rpm records, as well as 33 and 45 rpm vinyl records. The cover designs will be an opportunity for Ghanian graphic designers, illustrators, and photographers to make themselves known. In the 1980s, the production of audio tapes and digital technology will announce the decline of the vinyl industry.

Carmelle Bégin (10)

Reference sources

Cole, Catherine M. 2001. Ghana’s Concert Party Theatre. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Collins, John. 1992. West African Pop Roots. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Collins, John. 1994. Highlife Time. Accra: Anamsesem Publications Limited.

Collins, John. 1996. E.T. Mensah: King of Highlife. Accra: Anansesem Publications Limited.

Plageman, Nathan A. 2012. Highlife Saturday Night: Popular Music and Social Change in Urban Ghana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Veal, Michael E. 2000. Fela, The Life and Time of an African Musical Icon. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Carmelle Bégin © 2014 FDL

(1) Oscarmore Ofori was born on September 2nd 1930. He was a composer of highlife music and a guitarist. He played very nice highlife with calypso and jazz influences. He resided in London and published his album Afrika on EMI label in 1971. Oscarmore Ofori died in Ghana in 2007. (groovecollector.com)

(2) In the Northern Region, the Gumbe dance is entirely a highlife rhythm. The Adowa, an Ashanti traditional dance, has similarities of highlife both in the rhythm and the dance. The Ewe Agbaja has definite elements of highlife. Other forms of music, Asafo, Ntante, Ntae, Kete, etc. do show that they have contributed tremendously towards the building of highlife richness. The combination has evolved into something peculiarly Ghanaian. So when the slow moving rhythms of Black Beats Dance Band and the bouncing tempo of Broadway Dance Band creep to your bones, one should not wonder why. Oscarmore T.A. Ofori, 1971.

(3) The Arts Council of Ghana Law was entrusted to "foster, preserve, and improve" the nation’s cultural forms. In 1961, the Council moved to limit foreign music’s prominence by encouraging dance bands to infuse highlife with "traditional rhythms and dancing". N. Plageman, p.243.

(4) By 1930, southern urban areas had a large number of reputable dance bands that catered to club dances. Takoradi had the National Jazz Orchestra; Sekondi had the Optimum Club Orchestra and the Nanshamaq Orchestra; Cape Coast had the Rag-a-Jazzbo Orchestra, Professor Grove’s Orchestra, and the Cape Coast Light Orchestra (the Sugar Babies); Winneba had the Winneba Orchestra; Kumasi had the Warrab’s Orchestra and the Ashanti Nkramo Band; and Accra had the Excelsior Orchestra, Teacher Lamptey’s Accra Orchestra, the Jazz Kings and the Accra Rhythmic Orchestra. N. Plageman, p.107.

(5) From 1974 on, the Napoleon became the main musical centre of Accra. J. Collins, 1992, p.165.

(6) During this era concert parties made a dramatic transition from serving as British imperial propaganda honouring Empire Day to promoting Ghanaian cultural nationalism and the political career of Ghana’s first prime minister and president Kwame Nkrumah. C.M. Cole, 2001.

(7) Songs praising the leader, enhancing his reputation: Tempos: Nkrumah Highlife; Kwaa Mensah: Kwame Nkrumah; I.E. Mason: Ghana Mann; Fanti Stars: Nkrumah Ko Liberia; E.T. Mensah: Ghana Freedom Highlife, King Onyina: The Destiny of Africa. N.Plageman, p.220.

(8) Most conventional highlife compositions present a chord progression (a major key sequence alternating between tonic and dominant), up-tempo rhythm pattern, and bouncing introductory horn theme. Michael E. Veal, 2000.

(9) J. Collins, 1994, p.245.

(10) Ethnomusicologist working at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now Canadian Museum of History), I met Kwame Sarpong in 2001. He visited the museum with a gramophone and 78 rpm records of highlife music. This meeting was the starting point of museology exchanges and preventative conservation of recording collections with the Gramophone Records Museum and Research Centre, directed by Kwame Sarpong in Ghana. What followed was the repatriation in Ghana by the Canadian Museum of History of Asante artifacts that were stolen by British soldiers during the colonial wars. This collaboration was an opportunity for me to learn about highlife music. Without being a specialist of this music, I am sensitive to its somewhat old charm, which evokes the outdated style of Cuban band Buena Vista Social Club.

Index:

- Foreword

- Historical Background

• About the Museum

• Ghanaian Traditional Music

• Highlife Music - Finding Aids in the Highlife Collection

• Music selection

• Ghanaian music album sleeves

- Part 1

- Part 2

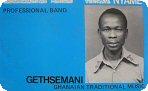

• Biographies and Interviews